Upon its creation in 1935, The Bright Stream, a ballet co-written by Fyodor Lopukhov and Adrian Piostrovsky to a score by Shostakovich, had difficulties. That comic expression in mime form does not always translate well in lengthy doses was only part of the problem. Fitting music and choreography to the state-sanctioned dictate of socialist realism resulted in an awkward combination. An early review in Pravda critiqued the art form of ballet as one built on dolls rather than people, and this ballet in particular as “a game with dolls” in which the depiction of collective farm workers was too character-esque to be believable or truthful. It was, in short, a “nonsense ballet.”

Upon its creation in 1935, The Bright Stream, a ballet co-written by Fyodor Lopukhov and Adrian Piostrovsky to a score by Shostakovich, had difficulties. That comic expression in mime form does not always translate well in lengthy doses was only part of the problem. Fitting music and choreography to the state-sanctioned dictate of socialist realism resulted in an awkward combination. An early review in Pravda critiqued the art form of ballet as one built on dolls rather than people, and this ballet in particular as “a game with dolls” in which the depiction of collective farm workers was too character-esque to be believable or truthful. It was, in short, a “nonsense ballet.”

For the most part, today, that remains true. Yet, from a historical point of view, Alexey Ratmansky’s 2003 revival of The Bright Stream holds merit.

Shostakovich, in his 1935 programme commentary, stated that he felt his score was “lighthearted, entertaining and, most important, danceable.” Yet he added that he disliked pure pantomime without dance. While his music is undoubtedly expert, the revised version of Stream by Ratmansky from 2003 purposely retains the weaknesses of the original. Part of that is not the fault of pantomime, but due to an overlong composition focusing almost entirely on comic farce with an insubstantial plot. Even after reviewing the libretto three times, it remains difficult to follow the intrigue among eight couples against the backdrop of this rural collective farm in the North Caucasus. The group dancing sections are colourful but plot-wise purposeless ensemble sections. The moral of the libretto lies in the fact that Zina, the main character, is in fact both a hard working collective farm participant and a good ballerina. Depth is not one of this libretto’s strengths.

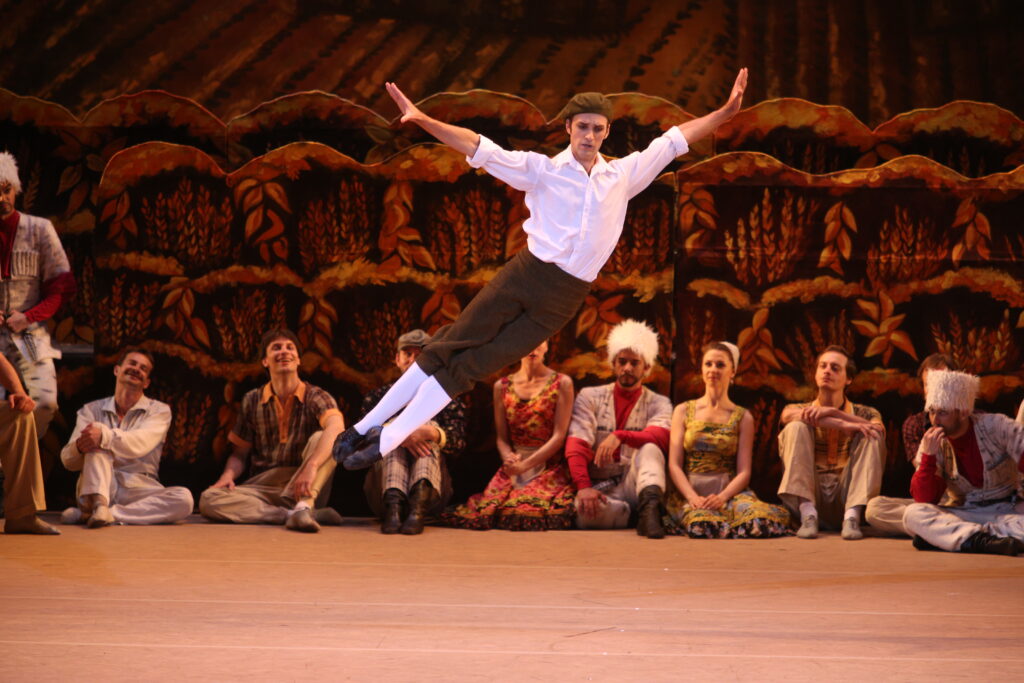

But on the Bolshoi dancers, there were unarguably moments of dancing virtuosity despite the wobbly structure of Stream. The ever slender, lithe and mobile Anastasia Stashkevich danced a vivid, simple Zina on the 8th of March next to Vyacheslav Lopatin’s ever-optimistic Pyotr. As the Classical Dancer, Kristina Krevtova appeared strong, with relaxed hands and an expressive countenance. Their duet together in Act I, attempting to recall steps from their Imperial Ballet School days, is a charming canon. Ruslan Skvortsov as the male Ballet Dancer displayed adroitness in his jumps. To his credit, Ratmansky excels in the crowd scene choreography: here Shostakovich’s rhythm comes to life, etched in space by the colourful kolhozi. And later, the male-male duet between Pyotr and the Old Dacha-Dweller (danced by Alexey Loparevich) displays moments of true comic and choreographic genius. It is this section that separates the proverbial wheat from the chaff, where illusions to La Sylphide lend substance to the dance and the characters.

But on the Bolshoi dancers, there were unarguably moments of dancing virtuosity despite the wobbly structure of Stream. The ever slender, lithe and mobile Anastasia Stashkevich danced a vivid, simple Zina on the 8th of March next to Vyacheslav Lopatin’s ever-optimistic Pyotr. As the Classical Dancer, Kristina Krevtova appeared strong, with relaxed hands and an expressive countenance. Their duet together in Act I, attempting to recall steps from their Imperial Ballet School days, is a charming canon. Ruslan Skvortsov as the male Ballet Dancer displayed adroitness in his jumps. To his credit, Ratmansky excels in the crowd scene choreography: here Shostakovich’s rhythm comes to life, etched in space by the colourful kolhozi. And later, the male-male duet between Pyotr and the Old Dacha-Dweller (danced by Alexey Loparevich) displays moments of true comic and choreographic genius. It is this section that separates the proverbial wheat from the chaff, where illusions to La Sylphide lend substance to the dance and the characters.

In all, The Bright Stream is worth a viewing from a historical perspective, for fans of the socialist realism heritage, and of course for lovers of Shostakovich. But ballets such as La Fille Mal Gardée may remain the preferential choice if looking for a comedy that does not veer as far from the classical heritage.