All photos courtesy of Mariinsky Theatre, by photographer Alexander Neff.

Over the past 300 years, there has not been a single war during which Russian ballet stopped its activity.

Just after the Great Russian Revolution of 1917, Agrippina Vaganova helped save the Imperial Ballet from dying at the hands of the new Soviet regime by creating a new methodology within the Leningrad Choreographic School, and “updating” classical ballets such as Swan Lake and Esmeralda, in order to make them easily digestible by the proletariat. During World War II, ballet students evacuated far from the front lines to the city of Perm, where they continued to study and train, planting the seeds for the preservation of Vaganova’s methodology in the theatre there.

And today, despite world events, Russia’s ballet theatres continue to support their classical traditions while seeking to implement “modern” trends from the West. Ironically, whereas during the Soviet era, it was the local Soviet government that prevented Russian and Ukrainian citizens from travelling abroad, now it is Europe and America who prevent Russian ballerinas and their cavaliers from continuing annual tours to Western cities, thereby isolating the beauty of this centuries-old art form to places within Russia’s borders. The dancers themselves play no role in the politics of big men with big weapons, yet it is they who suffer from it.

Alexander Sergeev’s heroic efforts in his experimental new work, a ballet called “12” based on the poem by Alexander Blok, are praiseworthy especially during this year of great turmoil. The dynamic Mariinsky dancer, a leading level soloist who has a number of choreographic compositions already under his belt, undertook the daunting task of reviving a ballet by Leonid Jakobson from the mid-1970s. The core idea of the work is, in Sergeev’s words, “not about Katya, Peter and Ivan, but about the fact that people periodically destroy the world with their own hands.” This “sense of something being destroyed” is depicted in the last section of the ballet, after forming the foundation of “something created” in Part I. Though only a 7-minute video remains from Jakobson’s original piece, Sergeev created a full-length work using the original score with additional music by the same composer, Boris Tishenko. The ballet is structured in three sections. Part I, with mezzo soprano Irina Shishkova singing to the onstage accompaniment of pianist Anatoliy Kuznetsov, features a couple dressed in white, the color presumably symbolizing the purity of a new union and true love. They are framed by rods of white light that form a box around them. The music to this section, “Three Pieces to the Poems of Marina Tsvetayeva” depicts the emotional, heartfelt connection between a young couple who part ways at the end. Maria Shirinkina danced the subtle, abstract movements in this section with surprising maturity, suggesting perhaps surprisingly that the contemporary genre –or at least this particular choreography– is one of her greater strengths. Her partner, veteran Maxim Zuizin, mirrored her in both sharp and fluid undulations. Hands fluttered to indicate a bird’s flight, then several balancés suggested the calm of early devotion, before the couple embraced, touching palms as Romeo and Juliet do, and backed away in a final separation. This prelude sets the tone for Parts II and III.

Alexander Sergeev’s heroic efforts in his experimental new work, a ballet called “12” based on the poem by Alexander Blok, are praiseworthy especially during this year of great turmoil. The dynamic Mariinsky dancer, a leading level soloist who has a number of choreographic compositions already under his belt, undertook the daunting task of reviving a ballet by Leonid Jakobson from the mid-1970s. The core idea of the work is, in Sergeev’s words, “not about Katya, Peter and Ivan, but about the fact that people periodically destroy the world with their own hands.” This “sense of something being destroyed” is depicted in the last section of the ballet, after forming the foundation of “something created” in Part I. Though only a 7-minute video remains from Jakobson’s original piece, Sergeev created a full-length work using the original score with additional music by the same composer, Boris Tishenko. The ballet is structured in three sections. Part I, with mezzo soprano Irina Shishkova singing to the onstage accompaniment of pianist Anatoliy Kuznetsov, features a couple dressed in white, the color presumably symbolizing the purity of a new union and true love. They are framed by rods of white light that form a box around them. The music to this section, “Three Pieces to the Poems of Marina Tsvetayeva” depicts the emotional, heartfelt connection between a young couple who part ways at the end. Maria Shirinkina danced the subtle, abstract movements in this section with surprising maturity, suggesting perhaps surprisingly that the contemporary genre –or at least this particular choreography– is one of her greater strengths. Her partner, veteran Maxim Zuizin, mirrored her in both sharp and fluid undulations. Hands fluttered to indicate a bird’s flight, then several balancés suggested the calm of early devotion, before the couple embraced, touching palms as Romeo and Juliet do, and backed away in a final separation. This prelude sets the tone for Parts II and III.

Following the live recitation of Blok’s jarring words by the “Reader” in Part II (on 22 September, read by Honored Artist Ekaterina Kondaurova and on October 1 by Sergeev himself), Part III depicts the action of the poem assisted by stage sets based on a module theme. Giant white blocks serve as a building when stacked up, a table when placed side-by-side, grey containers when unlit, or modern ceiling lamps when hung from above. It is up to the viewer to determine the exact meaning of each configuration.

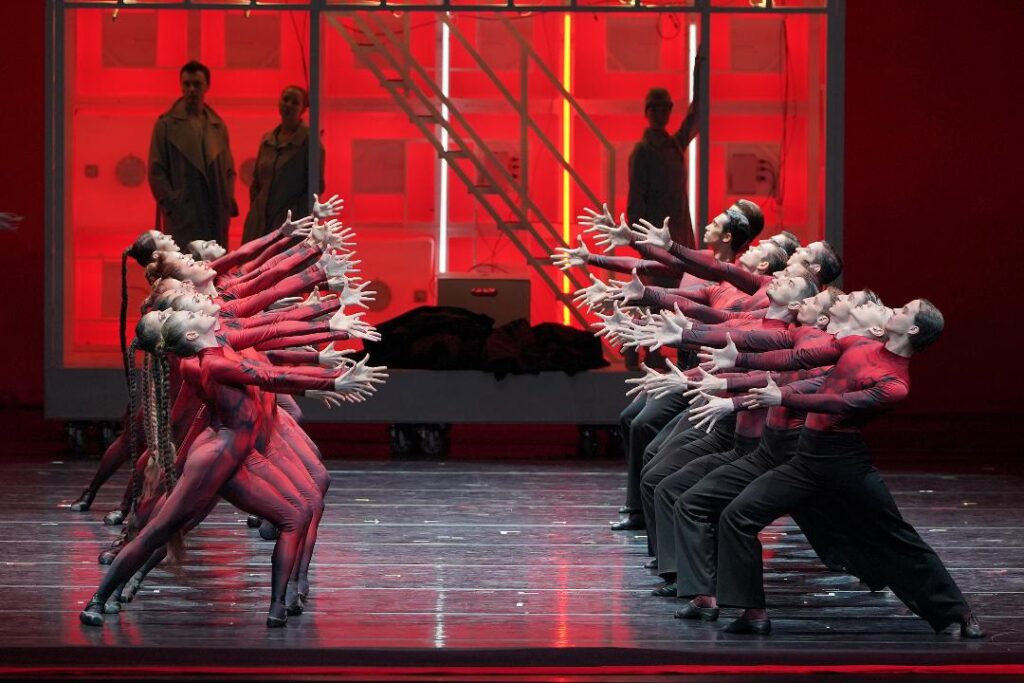

The abstract setting creates a performance in which the viewer must participate in order to fully comprehend, but even those previously unfamiliar with Blok’s poetry will easily understand the essence of the work based on the events danced in Part III. Echoes of both “Leningrad Symphony” and “Sacre du Printemps” come into play here, where the group of 12 women clasp hands and circle each other in a unified sense of solidarity –they could be in mourning over soldiers sent to the front, but the more likely setting is women in prison awaiting their sentence– before one is singled out and killed following a brief dalliance with “Petya” during a frenzy that rises to fever pitch (“Petya” is the Russian diminutive for Pyotr, or Peter). Petya, danced on 22 September by Alexei Timofeyev, arises from the front row of the Orchestra seats and walks across the orchestral bridge to reach the stage for his duet with her. Filled with exhausting lifts and complex movements, this duet suggests a sensual interlude that should be hidden, but is noticed and punished.

The abstract setting creates a performance in which the viewer must participate in order to fully comprehend, but even those previously unfamiliar with Blok’s poetry will easily understand the essence of the work based on the events danced in Part III. Echoes of both “Leningrad Symphony” and “Sacre du Printemps” come into play here, where the group of 12 women clasp hands and circle each other in a unified sense of solidarity –they could be in mourning over soldiers sent to the front, but the more likely setting is women in prison awaiting their sentence– before one is singled out and killed following a brief dalliance with “Petya” during a frenzy that rises to fever pitch (“Petya” is the Russian diminutive for Pyotr, or Peter). Petya, danced on 22 September by Alexei Timofeyev, arises from the front row of the Orchestra seats and walks across the orchestral bridge to reach the stage for his duet with her. Filled with exhausting lifts and complex movements, this duet suggests a sensual interlude that should be hidden, but is noticed and punished.

The tireless stamina and utter mastery of both emotional and choreographic text by Konstantin Zverev in the role of Petya deserves special mention. He discards women, including Katka, with hatred, as if swatting off flies. But in his monologue following Katka’s death, he wipes his hands nervously as of trying to wipe off blood, and when guilt hits, his scornful violence shift to immediate fear –hands wringing around his head in regret, depicted with such clarity that it’s easy to feel the same emotions along with him.

Moments of mastery in Sergeev’s choreography, especially in wide-ranging emotional displays by leading characters, appear throughout Part III, but most powerful is the firing squad ending, in which 12 men (clothed initially in long winter top coats) face the audience with steely grins, and fall one-by-one as if shot, each on a different musical note, only to stand back up again as if they are rubber soldiers in a children’s game. After all lie inert, the apotheosis comes when Reader strolls in to embrace the soul of now-deceased Katka (now adorned in a spare flesh-colored bikini) in a final duet, offering closure to the ballet if not to the topic itself.

Sergeev has much to be proud of: a work of this depth and expansiveness, rooted in literature, using multimedia layesr of sound, light and movement to demonstrate one of humanity’s unfortunately repetitive themes: the cycle of life and death, the destructiveness of man, and yet at the core of it all, a birth of love. Even if you are a diehard classisist, “12” is a masterpiece within its own genre, and worth seeing for its complexity and the talent inherent in its composition.