In 2018, as Russia celebrated the “Year of Petipa” in honor of Marius Petipa’s 200th birthday, the annual Mariinsky Ballet festival was cancelled and replaced with a handful of Petipa works. This year, the festival returned to the Mariinsky stage in Russia’s northern capital on 21 March, issuing in 10 consecutive evenings of ballet.

In 2018, as Russia celebrated the “Year of Petipa” in honor of Marius Petipa’s 200th birthday, the annual Mariinsky Ballet festival was cancelled and replaced with a handful of Petipa works. This year, the festival returned to the Mariinsky stage in Russia’s northern capital on 21 March, issuing in 10 consecutive evenings of ballet.

Head of the troupe, Yuri Fateev, long ago stated he views the Mariinsky not as the holder of Russia’s Petipa traditions, or the recipient of the Vaganova Academy’s best graduates — although arguably it should include both– but aims to make it into the “ABT of Russia”. This festival has shown just how much he has moulded the company towards that vision since he took on his position in 2007. Gone is the all-Russian roster and in its place a conglomeration of international graduates, punctuated by international guest artists during this particular festival.

The first two nights, titled “An Evening of American Choreography”, eschewed classical traditions and replaced them with importations from the New World. American Choreography opened with Balanchine’s Serenade, before shifting to Robbins’ In the Night and concluding with the Mariinsky premiere of Twyla Tharp’s When Push Comes to Shove. Serenade, which premiered some 21 years ago on this stage, looked relatively fresh despite a few moments of asynchrony from the new set of corps members who just recently learned the choreography. The corps did have moments of sparkle however, such as the coupé fondu/relèvé écarté to arabesque sequence in which the ladies managed to etch identical lines. New York City Ballet’s Maria Kowroski, presumably performing the steps exactly as Balanchine intended –fingers splayed in contrast to “Vaganova style” hand positions, and arabesque carved differently from the square-ness of the Russian school– attacked her steps with drive and focus. Kowroski first danced on the Mariinsky stage over 12 years ago in Rubies, and still appears in good form.

Anastasia Nuikina, one of famous pedagogue Ludmila Kovalyova’s graduates (Kovalyova is perhaps best known for coaching Diana Vishneva), debuted in Serenade during this performance. Nuikina is a tall, sprightly jumper, one might say a Balanchine dream: a simple plié is sufficient to propel her well off the floor. In the set of sautés with her head dipping forward to a leg brushed into battement devant, she appeared not only an essay in gymnastic form but an agile athlete. Delicacy and sensitivity may not be her foray, but petit and grand allegro are. Yekaterina Chebykina also debuted, performing the dark angel section with direction and command; Alexander Romanchkov rounded out the list of soloists on opening night. During the dark angel section, Kowroski directed her gaze upward to Romanchikov as if he were a savior, but the second that Chebykina waved her “wings” and covered his eyes, Kowroski’s head turned downward, the illumination of the moment gone. At the ballet’s close, when three men enter to lift Kowroski on their shoulders and carry her toward the upstage light, the image seems to be a metaphor for heaven’s salvation, though there is to date no established explanation for the symbolism. Gavriel Heine led the orchestra in a pure rendition of this heavenly Tchaikovsky score.

In the Night is not new to the Mariinsky repertoire and in fact has run routinely on its stage over the past decade. Jerome Robbins’ work remains as infectious for its philosophical explorations as for its movement-based commentary on three types of relationships. As the first couple, Vladimir Shklyarov accompanied sparrow-like Maria Shirinkina in a tender, harmonious duet. They infused their interaction with love and gentle unity, her positioning careful and his partnering attentive. The steadfast Konstantin Zverev accompanied Alina Somova in the second, stern duet, where his gallantry outshone her loose limbs. As the passionately feuding couple, Viktoria Tereshkina joined veteran Danila Korsuntsev, hitting all of the musical accents with precision, and providing a keen contrast between their fiery entry and the calm moment of reconciliation at the end.

In the Night is not new to the Mariinsky repertoire and in fact has run routinely on its stage over the past decade. Jerome Robbins’ work remains as infectious for its philosophical explorations as for its movement-based commentary on three types of relationships. As the first couple, Vladimir Shklyarov accompanied sparrow-like Maria Shirinkina in a tender, harmonious duet. They infused their interaction with love and gentle unity, her positioning careful and his partnering attentive. The steadfast Konstantin Zverev accompanied Alina Somova in the second, stern duet, where his gallantry outshone her loose limbs. As the passionately feuding couple, Viktoria Tereshkina joined veteran Danila Korsuntsev, hitting all of the musical accents with precision, and providing a keen contrast between their fiery entry and the calm moment of reconciliation at the end.

It was Mikhail Baryshnikov who first popularized When Push Comes To Shove decades ago in the US on television, his nonchalant physical mastery of the casual jazz style made capable only against the backdrop of deeply engrained classical training. This Twyla Tharp ballet is a vaudeville-esque combination of now-balletic, now-jazzy steps set to a score by Joseph Lamb and Joseph Haydn.

It was Mikhail Baryshnikov who first popularized When Push Comes To Shove decades ago in the US on television, his nonchalant physical mastery of the casual jazz style made capable only against the backdrop of deeply engrained classical training. This Twyla Tharp ballet is a vaudeville-esque combination of now-balletic, now-jazzy steps set to a score by Joseph Lamb and Joseph Haydn.

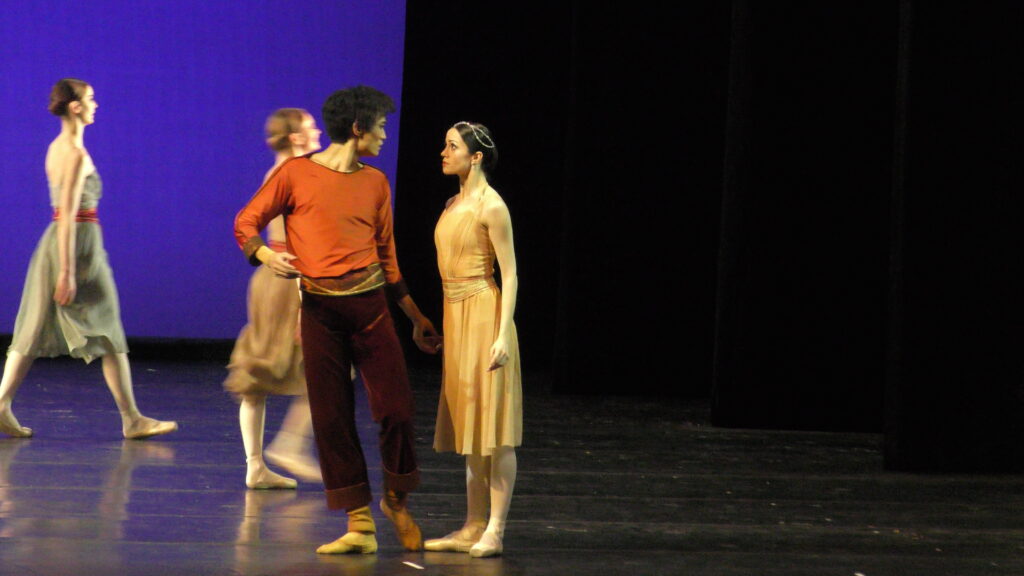

On 21 March, Kimin Kim assumed the main role, clearly executing Tharp’s choreography without a hitch. There were moments of expressiveness and flirtation along with agility in a star-level set of brisés. The steps clearly take Kim –and indeed most of the troupe– outside their comfort zone, but nevertheless this jumping powerhouse coped well. First soloist Nadezhda Batoeva, the ever-reliable spice queen, danced a jazzy accompaniment to Kim, even her eyes dancing to the beat. If there is effort behind Batoeva’s dancing, it’s never visible, for her expressive movement and steely technique are second nature. Tatiana Tkachenko recalled her own performances as the night club beauty in Young Girl and a Hooligan, here emitting the same sultry attitude with sharp shifts to austerity alongside Konstantin Zverev in a short duet. The marching music with 8 corps members in pseudo-medieval dress, halfway through, set to chamber music tunes suggested a more grounded sort of movement, and the group of 8 ladies with red sashes highlighted the snappy petit allegro tempi with precision. Resident conductor Gavriel Heine turned the score for Push into electrifying, jazzy accompaniment that few orchestras would be able to match.

One wonder of the Mariinsky is its ability to carry out nearly any choreography decently, and Shove is no exception. But whereas Western troupes are nearly all capable of carrying out the forgiving step combinations in more modern styles, these elite bodies are capable of far more. No other house in the world is home to the heritage of Petipa, no other company can render his classics as idyllically as they were intended as the Mariinsky. The troupe deserves kudos for their efforts to shift into a new movement language, and the result on opening night was certainly a success. Local viewers, however, are eager to see some of the classical works on the bill during the remainder of the festival.

One wonder of the Mariinsky is its ability to carry out nearly any choreography decently, and Shove is no exception. But whereas Western troupes are nearly all capable of carrying out the forgiving step combinations in more modern styles, these elite bodies are capable of far more. No other house in the world is home to the heritage of Petipa, no other company can render his classics as idyllically as they were intended as the Mariinsky. The troupe deserves kudos for their efforts to shift into a new movement language, and the result on opening night was certainly a success. Local viewers, however, are eager to see some of the classical works on the bill during the remainder of the festival.

Top photo and image of Kimin Kim with Nadezhda Batoeva, with the kind courtesy of the author’s permission, thank you to Vlada. All other photos Valentin Baranovsky and Natasha Razina courtesy of the Mariinsky Theatre.